We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

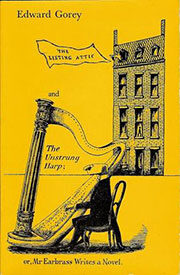

The Unstrung Harp Edward Gorey On November 18th of alternate years Mr. Earbrass begins writing his new novel. Weeks ago he chose its title at random from a list of them he keeps in a little green note-book. It being tea-time of the 17th, he is alarmed not to have thought of a plot to which The Unstrung Harp might apply, but his mind will keep reverting to the last biscuit on the plate. So begins what the Times Literary Supplement called "a small masterpiece." TUH is a look at the literary life and its "attendant woes: isolation, writer's block, professional jealousy, and plain boredom." But, as with all of Edward Gorey's books, TUH is also about life in general, with its anguish, turnips, conjunctions, illness, defeat, string, parties, no parties, urns, desuetude, disaffection, claws, loss, trebizond, napkins, shame, stones, distance, fever, antipodes, mush, glaciers, incoherence, labels, miasma, amputation, tides, deceit, mourning, elsewards. You get the point. Finally, TUH is about Edward Gorey the writer, about Edward Gorey writing The Unstrung Harp. It's a cracked mirror of a book, and it's dedicated to RDP or Real Dear Person.

“The Unstrung Harp” is the first book in the collection Amphigorey, a compilation of Edward Gorey's work. The title Amphigorey comes from the word amphigory, which means a nonsense verse or composition. “The Unstrung Harp” is about the writing process of novelist Clavius Frederick Earbrass, and is considered a commentary on the literary creation process.

It is like working out! You do it every day. You’d never work out for 5 hours in one day — that would be unsustainable, but also just bad for you. Similarly, taking a month off is okay, but it’s going to really fucking hurt that first day back in there. None of this is fun. But it can feel good.

ANTHONY VEASNA SO

Writing is not typing. Thinking, researching, contemplating, outlining, composing in your head and in sketches, maybe some typing, with revisions as you go, and then more revisions, deletions, emendations, additions, reflections, setting aside and returning afresh, because a good writer is always a good editor of his or her own work. Typing is this little transaction in the middle of two vast thoughtful processes.

REBECCA SOLNIT

Why I Chose This Poem

Two opposed statements, both equally true. That's what I love about train rides: you're neither in the place you left nor in the place you're going to. For a while you're nowhere, and the world outside the window keeps on ending, then beginning again. You're just a passenger, and when you arrive you'll have to become yourself again.

In this provocative, witty, and sometimes rueful book, David K. Cohen

writes about the predicaments that teachers face. Like therapists,

social workers, and pastors, teachers embark on a mission of human

improvement. They aim to deepen knowledge, broaden understanding,

sharpen skills, and change behavior. One predicament is that no matter

how great their expertise, teachers depend on the cooperation and

intelligence of their students, yet there is much that students do not

know. To teach responsibly, teachers must cultivate a kind of mental

double distancing themselves from their own knowledge to understand

students’ thinking, yet using their knowledge to guide their teaching.

Another predicament is that although attention to students’ thinking

improves the chances of learning, it also increases the uncertainty and

complexity of the job.

The circumstances in which teachers and

students work make a difference. Teachers and students are better able

to manage these predicaments if they have resources―common curricula,

intelligent assessments, and teacher education tied to both―that support

responsible teaching. Yet for most of U.S. history those resources have

been in short supply, and many current accountability policies are

little help. With a keen eye for the moment-to-moment challenges, Cohen

explores what “responsible teaching” can be, the kind of mind reading it

seems to demand, and the complex social resources it requires.

Ansché Hedgepeth is appalled that despite her lawsuit, brutal child arrests continue in D.C.

Her case made international news and made her a figure in the confirmation of Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., who ruled in a 2004 opinion that Hedgepeth’s Fourth Amendment rights were not violated, even if the transit officers overreacted.

“No one is very happy about the events that led to this litigation,” Roberts, then a circuit judge on the U.S. District Court in D.C., wrote in that opinion.

“A twelve-year-old girl was arrested, searched, and handcuffed. Her shoelaces were removed, and she was transported in the windowless rear compartment of a police vehicle to a juvenile processing center, where she was booked, fingerprinted, and detained until released to her mother some three hours later — all for eating a single french fry in a Metrorail station,” Roberts wrote. “The child was frightened, embarrassed, and crying throughout the ordeal.”

I remember sitting in her bedroom talking to her. She had a science fair trophy by her bed and had never been in that kind of trouble before.

“I was embarrassed,” she told me back then. “[The officer] said: ‘Put down your fries. Put down your book bag.’ They searched my book bag and searched me. They asked me if I have any drugs or alcohol.”

Today, she is outraged.

Because 24 years later, despite a grueling court case she and her mother endured that forever changed Transit Police policy on arresting children, other behavior hasn’t changed much.

“It’s important to note police brutality is way worse now than when I was a child,” she said, upon learning of the horrific case of Niko Estep, who never recovered from the trauma of being arrested and humiliated — much like Hedgepeth was — when he was 9.

“What happened to Niko never should have happened. Niko wasn’t a threat to any of those officers, and their use of force was outrageous and unnecessary. The police are supposed to protect our community, and instead they traumatized Niko,” his mom, Autumn Drayton, said when she filed a lawsuit against police Wednesday, the exact 24-year anniversary of the day the young Ansché was arrested.

“He never fully recovered from the incident, and he went from being an outgoing and social little boy to being distant and withdrawn and terrified of authority figures and the people who were supposed to keep him safe,” Drayton told The Washington Post’s Ellie Silverman.

Two D.C. police officers came up to Niko when he was leaning against a car on an April day in 2019 and told him to move. He “made a disrespectful comment” and ran, according to Drayton’s lawsuit.

A video shows an officer, identified as Joseph Lopez in the suit, yanking the boy’s jacket, dragging him to the sidewalk after he fell, and placing handcuffs around his wrists as he cried and wet himself in fear.

That video made the rounds at school. Three months later, Niko was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric ward after attempting suicide, according to the lawsuit. D.C. police changed their policy on handcuffing children the following year. But the suit alleges these incidents still occur.

Niko was killed at 14 in an unrelated incident last year.

“I hate that that happened to him,” said Hedgepeth, who is now 36, an executive manager at a national association and a newlywed.

She remembered the tween discomfort of being the focus of a national incident as a seventh-grader.

“It was hard as a kid. Coming out and speaking about it, and it being in the news, triggered attention I didn’t want or need as a 12-year-old,” she said.

“Lots of teasing and being called ‘French Fry’ for years,” she said. “But for me, I was able to overcome. I was able to push through and continue with my life.”

She said she tucked the trauma of it away, “and eventually the teasing stopped. Every now and then the story resurfaces, and people are almost shocked that it was me,” she said.

When Hedgepeth was arrested, it was Transit Police policy to issue a citation to anyone caught eating on the Metro. The strict enforcement is largely tolerated and welcomed in a system known to be way cleaner than the more infamous filth on the one up north.

But the protocol for snacking kids in D.C. was arrest.

Hedgepeth had just bought a snack at the place where most Alice Deal Middle School kids hung out in 2000, and was finishing up the fries as she rode the escalator down to the busy Northwest D.C. metro station to head home.

That’s when the officer nabbed her during the first day of a systemwide crackdown on snacking.

“My principal wanted to suspend me from school. Metro [police] wanted it on my record. But none of those happened,” Hedgepeth told me. “I’m so grateful to my parents for advocating for me.”

Back then, Metro Transit Police Chief Barry J. McDevitt, was unapologetic for such arrests and told me, “We really do believe in zero tolerance.”

The absurd arrest made international headlines, and the family’s lawsuit led to a policy change.

“The incident was a catalyst for a warning system now in use,” Metro spokeswoman Candace Smith told me when I followed up in 2006, pointing to rule changes such that if police find a youth snacking illegally, they issue a written warning, after three of which the juvenile is charged.

That was the year my son, now a senior at Duke Ellington High School who rides the same Metro line that Hedgepeth rode, was born. Her arrest and dogged pursuit for change affects my kid’s crew of teens every day.

Hedgepeth would rather have nothing to do with her fry days, but agreed to talk with me this week because her case is a reminder that advocacy and a pursuit of justice can matter.

“I definitely made change,” she said. “And I’m forever proud of that.”

In an undated photo, first- and second-grade students sit in a classroom at the Genoa Indian Industrial School in Genoa, Nebraska. (National Archives/AP)

These remarks would be the first time a U.S. president has apologized for the atrocities suffered by tens of thousands of Native children who were forced to attend the boarding schools over several generations. From 1819 to 1969, the U.S. government managed or paid churches and religious groups to run more than 400 federal Indian boarding schools across 37 states.

“It’s extraordinary that President Biden is doing this,” said Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the country’s first Native American Cabinet secretary, in an interview with The Washington Post. “It will mean the world to so many people across Indian Country.”

Biden is set to make his historic announcement at the Gila Crossing Community School outside of Phoenix. The visit — his first to Indian Country as president — comes as Biden seeks to burnish his legacy before leaving office and boost his vice president’s campaign for the presidency less than two weeks before Election Day.

While Native American voters make up a small slice of the electorate, their votes could prove determinative in closely divided states such as Arizona. Biden’s move could have a reverberating impact with tribal members, whose votes are especially critical in North Carolina, Nevada, Michigan and other battleground states.

Biden won in Arizona in 2020 by less than 1 percentage point, carrying a state where Native Americans make up more than 5 percent of the population. The White House has billed Biden’s visit to the Gila River Indian Community as a promise kept, noting that his administration has given unprecedented amounts of funding to build roads and bridges, improve access to high-speed internet, and provide clean water for tribal communities.

For her part, Vice President Kamala Harris has sought to play up her record on issues important to Native Americans in recent campaign events, including a rally this month in Arizona. Former president Donald Trump and his Republican allies have also courted Native American voters during his presidential campaign, hoping to win over a group that typically leans Democratic.

Biden’s Friday event follows a report released by the Interior Department this summer that found that at least 973 Native American children, who were taken from their homes, died of disease and malnutrition at the schools. Many other children were physically abused, sexually assaulted and mistreated. The Interior Department urged the U.S. government this summer to formally apologize for the enduring trauma inflicted on Native Americans.

Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe of New Mexico whose grandparents and great-grandfather were taken from their homes and sent to boarding schools, launched the investigation three years ago, the first time the U.S. government had closely scrutinized the schools. Along with Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, Haaland spent more than a year traveling from Oklahoma to Alaska on a tour billed as “The Road to Healing.” At 12 stops, for up to eight hours a day, they listened to stories of emotional, physical and sexual abuse told by survivors and their descendants.

“I think the folks who suffered through that era personally — the survivors, the descendants — will feel seen by the president,” Haaland told The Post. “That’s something that a lot of people have not experienced in this country and throughout our history.”

By 1900, 1 in 5 Native American school-age children were sent to a boarding school, sometimes thousands of miles from their families. Children were stripped of their names and instead often assigned numbers. Their long hair was cut and they were beaten for speaking their languages, leaving deep emotional scars on Native American families and communities.

At least 80 of the schools were operated by the Catholic church or its affiliates. The Post, in a year-long investigation published in May, found at least 122 priests, sisters and brothers assigned to 22 boarding schools since the 1890s were later accused of sexually abusing Native American children under their care. Most of the documented abuse, which involved more than 1,000 children, occurred in the 1950s and 1960s.

About two weeks after The Post’s report, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a formal apology for the church’s role in inflicting a “history of trauma” on Native Americans. The document said, “We all must do our part to increase awareness and break the culture of silence that surrounds all types of afflictions and past mistreatment and neglect.”

In 2022, Pope Francis traveled to Canada and apologized for the church’s role there in running boarding schools similar to those in the United States. But the pope has remained silent about the abuse at Catholic-run Indian boarding schools in the United States.

It is rare for a sitting American president to offer a formal apology for past national sins. In 1998, while speaking in Uganda, President Bill Clinton apologized for slavery in the United States and his country’s role in the trade of Africans.

On his trip to Phoenix, Biden is slated to be joined on Air Force One by Haaland and a group of tribal leaders from across the country, including Deborah Parker, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribes and the chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Native American advocates have also long been pushing for a formal presidential apology for the U.S. government’s role in creating and operating Indian boarding schools. In the spring, Parker met with Tom Perez, a senior adviser and assistant to Biden, at the White House and asked Biden to apologize for the widespread mistreatment and abuse that Native American children suffered at boarding schools.

But until now, the White House has been silent.

“It’s been a long time coming,” Parker said of the expected apology. “These schools were tools of assimilation and cultural genocide resulting in the loss of language and culture and the separation of children from their families.”

No one knows exactly how many Native American children attended the Indian boarding schools because many records were poorly kept, lost or destroyed. In the Interior report this summer, Newland’s team of researchers said it was able to identify 18,624 Native American children who were forced to attend the schools. But the report noted that the number of students was greater — and academic researchers who have studied this issue for years say the number is an undercount.

The Interior report also estimated that the federal government spent more than $23.3 billion, adjusted for inflation, over 98 years to implement the Indian boarding school system, similar institutions and associated assimilation policies.

Citing several studies, Haaland’s report highlighted the generational trauma of federal Indian boarding schools and other assimilation-related efforts, saying that these policies continue to fuel high suicide rates, drug abuse, alcoholism and poor parenting in Native American communities.

The report’s recommendations included funding for the teaching of tribal languages that the government tried to erase and the possible return of some former boarding school sites to tribes. The report’s authors also recommended a national memorial to educate Americans about the boarding school era and honor the children who died while attending the schools.

When Haaland was a member of Congress in 2020, she introduced legislation to create the first commission in U.S. history to investigate and document America’s Indian boarding schools.

The legislation was reintroduced last year in the Senate and this year in the House — but has not reached the floor for a vote in either chamber. The commission would have subpoena power, which could be used to compel the Catholic Church and other religious institutions that ran the schools to disclose their internal documents about boarding schools, experts said.

Administration officials said Biden planned to use his Arizona stop to tout his administration’s accomplishments for tribal nations, highlighting $32 billion in funding from the American Rescue Plan, the conservation of vast swaths of land significant to tribes, and the appointment of Haaland and other high-ranking Native American officials. Biden is also expected to praise the efforts of first lady Jill Biden, an educator who has visited tribal communities 10 times and pushed for Native language revitalization.

But the marquee moment Friday is the president’s expected apology, a long-awaited and welcomed message to many tribal leaders.

Stephen Roe Lewis, the governor of the Gila River Indian Community who comes from three generations of boarding school survivors, praised Biden’s plan to apologize.

“After four years, we’re finally getting an official apology from the president of the United States,” Lewis said. “Some of our elders who are boarding school survivors have been waiting all of their lives for this moment.”

“It’s going to be incredibly powerful and redemptive when the president issues this apology on Indian land,” Lewis said. “If only for a moment on Friday, this will rise to the top and the most powerful person in the world, our president, is shining a light on this dark history that’s been hidden.”

Tyler Pager contributed to this report.

“You wish your face was more—more, something. You don’t know what. Maybe

not more. Less. Less flat. Less delicate. More rugged. Your jawline

more defined. This face that feels like a mask, that has never felt

quite right on you. That reminds you, at odd times, and often after two

to four drinks, that you’re Asian. You are Asian! Your brain forgets

sometimes. But then your face reminds you.”

―

Charles Yu,

Interior Chinatown

“This is what I say: I've got good news and bad news.

The good news is, you don't have to worry, you can't change the past.

The bad news is, you don't have to worry, no matter how hard you try, you can't change the past.

The

universe just doesn't put up with that. We aren't important enough. No

one is. Even in our own lives. We're not strong enough, willful enough,

skilled enough in chronodiegetic manipulation to be able to just

accidentally change the entire course of anything, even ourselves.”

―

Charles Yu,

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe

“I don't miss him anymore. Most of the time, anyway. I want to. I

wish I could but unfortunately, it's true: time does heal. It will do so

whether you like it or not, and there's nothing anyone can do about it.

If you're not careful, time will take away everything that ever hurt

you, everything you have ever lost, and replace it with knowledge. Time

is a machine: it will convert your pain into experience. Raw data will

be compiled, will be translated into a more comprehensible language. The

individual events of your life will be transmuted into another

substance called memory and in the mechanism something will be lost and

you will never be able to reverse it, you will never again have the

original moment back in its uncategorized, preprocessed state. It will

force you to move on and you will not have a choice in the matter.”

Leave things lumpy. People want to know how the protagonist’s father’s dress socks looked against his pale white shins. People want to know the titles of the strange and eclectic books lining the walls of his study. People want to know the sounds he made while snoring, how he looked while concentrating, the way his glasses pinched the bridge of his nose, leaving what appeared to be uncomfortable-looking ovals of purple and red discolored skin when he took those glasses off at the end of a long day. Even if those lumps make the mixture less smooth, less pretty, even if you don’t quite know what to do with them, even if they don’t figure into your chemistry—they don’t have a place in the reaction equations—leave them there. Leave the impurities in there.

CHARLES YU

Constantly having fun. Even a sense of humor in his physics lectures. Besides being one of the last true Science geniuses, he: Loved a practical joke Loved drumming, and was quite skilled. The unicycle!

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

Remembering Patrick Kavanagh born on October 21 1904 - in Inniskeen, County Monaghan. “A man innocently dabbles in words and rhymes and finds that it is his life.”

I woke with what I call an anvil headache. It was a caffeine withdrawal headache. A sip of cold black coffee did the trick. Pain medicine would make me vomit on an empty stomach.

https://www.healthline.com/health/headache/caffeine-withdrawal-headache

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

Healthline only shows you brands and products that we stand behind.

Our team thoroughly researches and evaluates the recommendations we make on our site. To establish that the product manufacturers addressed safety and efficacy standards, we:You can find relief from a caffeine withdrawal headache with over-the-counter products and home remedies. Practices including stimulating pressure points may also help.

Although many people associate caffeine withdrawal with high levels of consumption, according to John Hopkins Medicine, dependency can form after drinking one small cup of coffee — about 100 milligrams of caffeine — a day.

Read on to learn how peppermint, ice, and other therapies can help ease your headache and reduce your reliance on caffeine overall.

Caffeine narrows the blood vessels in your brain. Without it, your blood vessels widen. The resulting boost in blood flow could trigger a headache or result in other symptoms of withdrawal.

Several OTC pain relievers can help relieve headache pain, including:

These medications are typically taken once every four to six hours until your pain subsides. Your dosage will depend on the type and strength of the pain reliever.

One way to ease a caffeine withdrawal headache — as well as other headaches — is to take a pain reliever that includes caffeine as an ingredient.

Not only does caffeine help your body absorb the medication more quickly, it makes these drugs 40 percent more effective.

It’s important to remember that caffeine consumption of any kind will contribute to your body’s dependence. Whether you let withdrawal run its course or resume consumption is up to you.

If you do take a pain reliever, limit your use to twice a week. Taking these medications too often can lead to rebound headaches.

Try it now: Purchase ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or aspirin.

Some research suggests that topical menthol — peppermint’s active ingredient — may help soothe headaches by reducing inflammation and relaxing tight muscles.

In fact, a 2016 study claims that topical peppermint oil may be as effective as acetaminophen at relieving tension headaches.

If you want to give it a try, gently massage two to three drops of peppermint oil into your forehead or temples. This oil can be safely applied without being diluted, though you’re welcome to mix it with a carrier oil (such as coconut oil).

Try it now: Purchase peppermint oil and a carrier oil.

If you regularly drink coffee or other caffeinated beverages, increasing your water intake can help reduce your risk for related headaches.

Caffeine can make you urinate more, increasing the amount of fluid you lose. Too little fluid in your body, or dehydration, can make your brain shrink in volume.

When your brain shrinks, it pulls away from your skull. This sets off pain receptors in the protective membrane surrounding the brain, which could trigger a headache.

The amount of fluid each person needs to stay hydrated can vary. A good rule of thumb is to drink eight glasses of water per day.

Ice is a go-to remedy for many people who get migraines. Applying an ice pack to your head can help ease headache pain by altering blood flow or numbing the area.

Another option is putting the ice pack on the back of your neck. In a small study, researchers placed a cold pack over the carotid artery in participants’ necks. The cold treatment reduced migraine pain by about a third.

Try it now: Purchase an ice pack.

Various points around your body correlate to your health. These are called pressure points, or acupoints.

Pressing on certain pressure points may help relieve headaches, in part by easing muscle tension. Researchers in a 2010 study found that one month of acupressure treatment relieved chronic headaches better than muscle relaxants.

You can try acupressure at home. One point that’s tied to headaches is located between the base of your thumb and your index finger. When you have a headache, try firmly pressing on this point for five minutes. Make sure you repeat the technique on the opposite hand.

Some people find that taking a nap or hitting the hay early can help relieve headache pain.

In a small 2009 study, 81 percent of participants with persistent tension headaches cited sleep as the most effective way to find relief. The relationship between sleep and migraine relief has also been noted.

That said, sleep has a peculiar connection to headaches. For some people, sleep is a headache trigger, and for others, it’s an effective treatment. You know your body best.

If other measures aren’t providing relief, you may consider giving in to your caffeine craving. Although this is a surefire way to soothe your symptoms, doing so will contribute to your dependence.

The only way to break this cycle is to cut back on or give up caffeine entirely.

Caffeine withdrawal symptoms may start within 24 hours of your last intake. If you quit cold turkey, symptoms may last up to a week.

Along with headaches, withdrawal symptoms can include:

Have more than one idea on the go at any one time. If it's a choice between writing a book and doing nothing I will always choose the latter. It's only if I have an idea for two books that I choose one rather than the other. I always have to feel that I'm bunking off from something.

Do it every day. Make a habit of putting your observations into words and gradually this will become instinct. This is the most important rule of all and, naturally, I don't follow it.

Never ride a bike with the brakes on. If something is proving too difficult, give up and do something else. Try to live without resort to perseverance. But writing is all about perseverance. You've got to stick at it. In my 30s I used to go to the gym even though I hated it. The purpose of going to the gym was to postpone the day when I would stop going. That's what writing is to me: a way of postponing the day when I won't do it any more, the day when I will sink into a depression so profound it will be indistinguishable from perfect bliss.