Phonetic alphabet: the story from Alpha to Zulu

https://www.theweek.co.uk/70110/alpha-bravo-charlie-how-was-natos-phonetic-alphabet-chosen

An older version began with Apples and Butter, while soldiers in the First World War preferred Ack and Beer

It's a familiar experience while watching war flicks - when the action kicks in, the dialogue devolves into a mass of Charlies, Deltas and Foxtrots.

But while dramatic licence may sometimes see these terms abused, the phonetic alphabet holds vital significance among militaries across the world - and has done for more than six decades.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) formally adopted the final version of the International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet - better known as the Nato phonetic alphabet or simply the Alpha, Bravo, Charlie alphabet - on 1 January 1956.

But Forces.net notes that “agreement on the words used was not entirely straightforward, with some words sparking strong debate”, and many of them have changed over time.

Here is how the words were chosen and how the alphabet has evolved.

What is the Nato phonetic alphabet for?

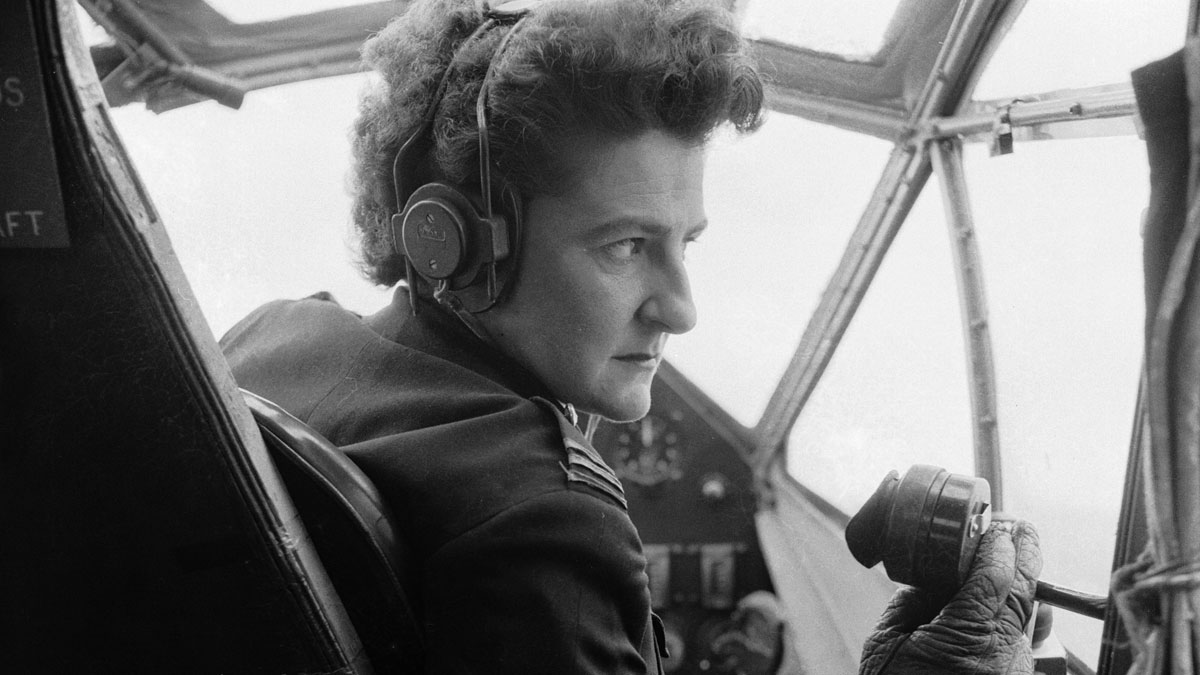

It was created as a standardised way for aircrews around the world to make themselves recognised and understood. All flights and planes are given names with identifying letters, but characters such as M and N or D and B can sound very similar, even when said by someone standing right next to you.

While not technically a phonetic alphabet (which helps individuals in the pronunciations of words), the Nato alphabet meant differences in accents, languages and pronunciations stopped being a problem.

Radio communications have moved on in terms of technical sophistication since then, but the alphabet is still in place in case of confusion, error or bad reception to make sure the correct message is transmitted, received and understood.

Why did it need to be standardised?

During the First World War, the Royal Navy used an alphabet that began Apples, Butter and Charlie, while British infantrymen in the trenches had their own version, which started Ack, Beer and Charlie.

The RAF developed an alphabet based on both of these but when the US air force joined the war, all Allied Forces adopted what became known as the Able, Baker alphabet. This also came to be used in civil aviation, but confusion continued, not least by the use of a separate English alphabet in South America.

Who made it up?

As an agency of the United Nations, it made sense for the ICAO to create a standardised alphabet, one which – even if made of English words – had sounds common to all languages and so could be spoken and pronounced internationally no matter what nationality the pilot. Jean-Paul Vinay of the University of Montreal, a noted professor of linguistics, was charged with creating a new alphabet equivalency list and completed it in 1951.

That new alphabet hit a spot of turbulence, though, as many pilots disliked it and reverted to the one they had been using previously. Consequently, after further study and testing among the 31 ICAO member countries, the current alphabet was officially introduced on the 1 March 1956, with just five simple changes to Jean-Paul Vinay’s earlier work – the words for the letters C, M, N, U and X.

Has it evolved since then?

Adopted worldwide, those changes have remained in place ever since and are still in use.

Over time it has, though, developed its own form of shorthand or slang, whereby certain combinations of the alphabet’s words have pre-established and inherent meaning.

For example, the expression “Oscar-Mike” means “on the move” and is used to denote a military unit, which is moving between positions.

These words and expressions “are also used outside the military, in areas of civilian life where it is also especially critical to ensure accurate and correct expression and understanding of words” says trivia site Sporcle.

This is true in the police force, where they have established their own Police Alphabet, in the financial sector, where banks and traders often use the alphabet for large transactions done over the phone, and in commercial airline communication as well.

The International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet:

A - Alfa (Alpha - the "ph" sound is not recognised internationally)

B - Bravo

C - Charlie

D - Delta

E - Echo

F - Foxtrot

G - Golf

H - Hotel

I - India

J - Juliett

K - Kilo

L - Lima

M - Mike

N - November

O - Oscar

P - Papa

Q - Quebec

R - Romeo

S - Sierra

T - Tango

U - Uniform

V - Victor

W - Whiskey

X - X-Ray

Y - Yankee

Z - Zulu

No comments:

Post a Comment