Businessweek + Green

An Age-Old Wool Recycling Tradition Offers Lessons for Fast FashionDemand for clothing made from repurposed fabrics is rising as awareness builds about textile waste.

By Aaron Clark and Flavia Rotondi

Mario Melani sits on a pile of folded blankets on the floor of a warehouse in Prato, Italy, surrounded by heaps of discarded wool sweaters and scarves. He deftly snips away buttons, zippers, embroidery and labels to strip the garments down to the cloth. It’s a critical step in the transformation of used wool into new fabrics, a tradition of textile makers in the Tuscan city that dates to the middle of the 19th century. “The alternative for all this would be the bin,” Melani says.

At 94, Melani has spent more than six decades working as a cenciaiolo, or ragman, a term that belies the local sense of pride in artisans like him, who can recognize a material’s composition just by touching it. Prato counts more than 7,000 companies that specialize in some part of the city’s clothing and textile industries—of which wool recycling plays a major role—including the small family business Melani owns, F.lli Melani Sauro e Simone & C.

In Prato, making new fabric from used wool generally follows this process: The garments are manually stripped, and the scraps are mechanically shredded. Next, those fibers are blended by color to get the desired hue. After a carding machine untangles and aligns the fibers in one direction, the material is spun into yarn and undergoes quality tests before being woven on a loom into a textile.

Historically, the global recycling of wool has been driven by economic opportunity and necessity, such as during disruptions in the fleece trade. Now, environmental concerns are spurring demand for recycled wool as consumers seek out clothes made primarily of reused natural fibers instead of synthetic materials, many of which can be recycled only through expensive, complex processes that involve chemicals.

Textile makers that give wool a second life can’t keep up with the interest, says Dalena White, secretary general of the International Wool Textile Organisation, a trade group that identifies wool recycling hubs in Italy, Germany, Thailand and Pakistan but doesn’t track volumes recycled. “It’s a growing trend. It’s happening everywhere.”

Environmental Footprint of a Wool Sweater

Wool accounts for only about 1% of global textile fiber production, so recycling discarded wool garments can’t offset the environmental impact of the global fashion industry. That sector generates an estimated 10% of the world’s carbon emissions and churns out more than 100 billion apparel items each year, or roughly 14 for every person on Earth, with tens of millions of garments tossed out every day to make way for new ones.

Still, the wool recyclers’ approach offers a circular economy model that can be emulated. As part of its effort to combat climate change, the European Union last year adopted a strategy for sustainable and circular textiles that lays out future actions by the commission, including setting requirements to make textiles easier to recycle and giving consumers information about a product’s raw materials, manufacturing and recycling through a so-called digital product passport. In terms of raw material use and greenhouse gas emissions, the consumption of textiles has the fourth-biggest impact on the environment and climate in the EU, after food, housing and mobility, according to the bloc.

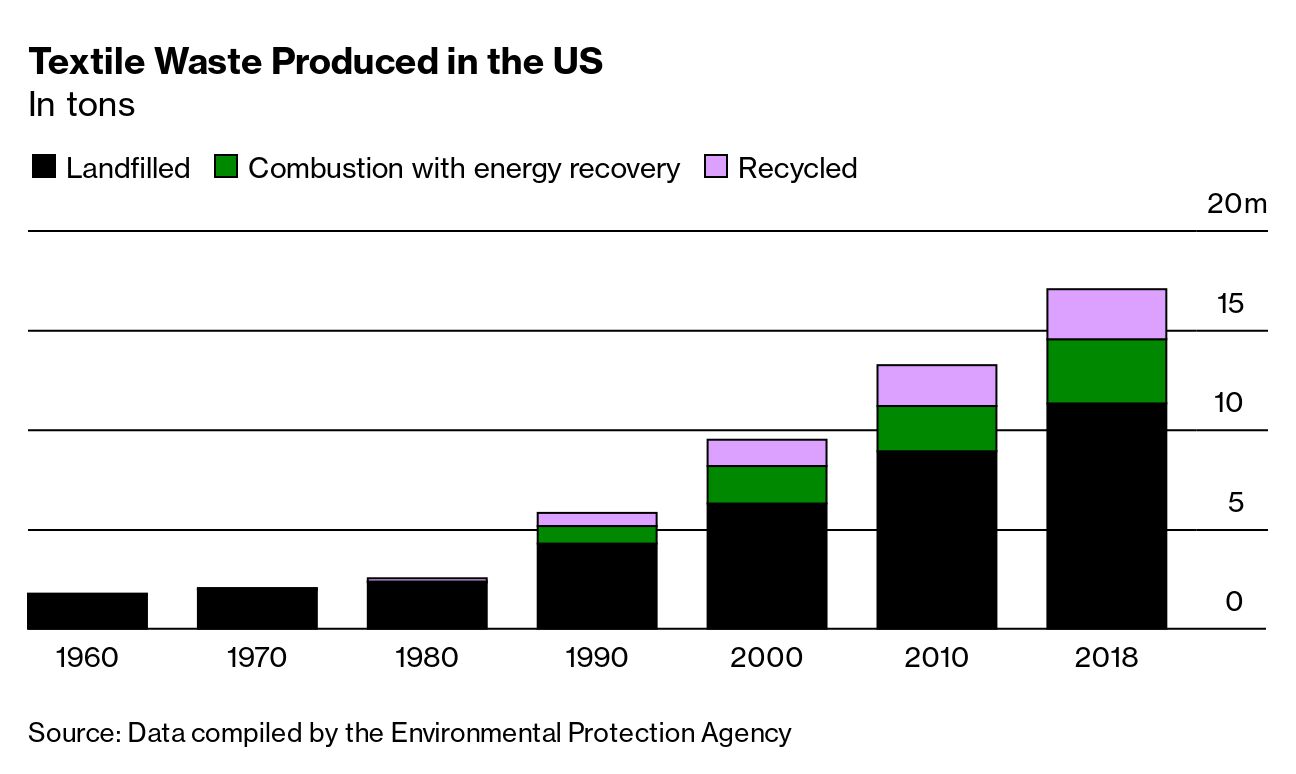

Textile Waste Produced in the US

In tons

“We need stricter regulations in the industry. The final consumer must become more aware of where a garment comes from,” says Marco Mantellassi, who is co-chief executive officer of Manteco SpA, a third-generation, family-owned textile producer in Prato, with his brother Matteo. Manteco counts Kering SA and LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE among buyers of fabrics it produces from its MWool-branded recycled wool. The company, which also makes fabrics from materials including viscose, lyocell and recycled and virgin cotton, recorded revenue of €97 million ($104 million) in 2022.

Depending on the quality of the second-hand wool it’s using, Manteco may include virgin wool and recycled or virgin nylon in some of its products. The company also recycles scraps generated when apparel companies cut clothes from bolts of fabric. Mantellassi says Manteco’s strict controls during the production process, as well as technological innovations, allow it to create luxury fabrics from recycled wool. “A circular economy is important, but if you don’t offer a nice product to the client they won’t buy it.”

Manteco says its recycled wool has a significantly lower carbon footprint than those of virgin wool and many other textiles. Producing a kilogram of its MWool generates 0.62 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent—a measurement used to compare various greenhouse gases—while the same amount of fleece sheared from a sheep creates 75.8kg of CO2e, the company says in its life-cycle assessment study. Cotton and polyester generate 4.69kg of CO2e and 4.31kg of CO2e, respectively, the company says, citing data from life-cycle inventory database provider Ecoinvent.

Identifying which materials are best for the environment isn’t straightforward, as the impacts of processes and supply chains aren’t always comparable, and recyclability is just one element to consider when assessing sustainability. For example, while wool can be recycled mechanically, the more than 1 billion sheep involved in its production globally produce burps containing methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Synthetic materials, on top of not being easily recycled, can shed microplastics in the wash—a menace to ocean creatures that’s not an issue with natural fibers.

“It’s not apples to apples,” Del Hudson, executive vice president of market impact for Worldly Holdings Inc., a technology platform that aggregates materials data for businesses to better understand the impacts of supply chains, said in an email. Sustainability claims should be treated with caution, according to Worldly, as they can fail to reflect real-world impacts that aren’t binary.

Although recycling textiles tends to have a lower environmental burden than producing new materials, the mechanical process for reconstituting wool results in a shorter fiber length than virgin fleece. This limits the number of times you can recycle the material, according to Joël Mertens, director of Higg Product Tools, a suite of data-driven analytics for brands that help measure the sustainability of apparel, footwear and textiles, which is owned by the Sustainable Apparel Coalition. This extends the life of the existing materials but doesn’t fully replace the need for new fibers, Mertens said in an email.

To boost textile recycling, clothing designers and apparel brands need to communicate better about how to increase the circularity of materials and supply chains, says Hasnain Lilani, the founder of Karachi-based Datini Fibres, which sells recycled wool fibers that it extracts from used garments and also conducts research on the sustainability of materials. The company, started two years ago after Lilani had worked as a textile trader, currently recycles from 3,000 tons to 5,000 tons of wool garments per year and hopes to expand operations to 10,000 tons by 2024.

“The real sustainable solutions are coming from the material producers and recyclers working with raw materials and post-consumer products,” Lilani says. “Fashion brands need to listen and invest in the back end for more sustainable supply chains.”

Editor: Rebecca Penty

Photo Editor: Donna Cohen

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment